| Come and Hear™ to increase interfaith understanding http://www.come-and-hear.com This page has been scanned from The Jewish Encyclopedia (1901-1906) to ensure availability for future students of Come and Hear™ |

Dilling Exhibit 285 Begins |

these are sometimes indicated; thus one charm was to be written on a red plate, another on a silver plate, and so on. By the employment of these amulets, paralysis, sciatica, eye and ear ailments, leprosy, and other evils were to be cured. With a certain plate fastened around the thigh, a man might enter a fiery furnace and come out unscathed. Material and inscription of the Amulet varied according to its purpose. By its means fish could be caught; the love of a woman secured and retained; the sea crossed dry-shod; wild animals slain; terror diffused through the world; communion had with the dead; a sword obtained which would fight automatically for its owner; one’s enemies set to tearing each other to pieces; oneself rendered invisible; springs of water found; cleverness attained; and many similarly wonderful things accomplished. In one passage a device that is frequently met with in Babylonian and Egyptian magic is mentioned; namely, the preparation of an image and working the charm desired by its medium. The prescription runs:

“If thou desirest to cause any one to perish, take clay from two river banks and make an image therewith; write upon it the man’s name; then take seven stalks from seven date-trees and make a bow [here follows the word [Hebr.]] with horsehair (?); set up the image in a convenient place, stretch thy bow, shoot the stalks at it, and with every one say the prescribed words, which begin with [Hebr.] and end with [Hebr.], adding, ‘Destroyed be N., son of N.!’”

Gaster (l.c. pp. 12-19) explains why these means were thought to be effective. It appears that every angel and demon is bound to appear and obey when he hears a certain name uttered (p. 25, lines 2-10). Even Hai Gaon (“Responsen der Geonim,” ed. Harkavy, 373, p. 189) says, “Amulets are written, and the divine name is spoken, in order that angels may help.” But a great deal was made to depend upon using the right name at the right time, a condition likewise frequently insisted on in the Egyptian and Babylonian magical works.

“Practical Cabala,” or the art of employing the knowledge of the hidden world in order to attain one’s purpose, is founded upon the mysticism developed in the “Sefer Yezirah” (Book of Creation). According to this work, God created the world by means of the letters of the alphabet and particularly those of His name, [Hebr.], “, which He combined in the most varied ways. If one learns these combinations and permutations, and applies them at the right time and in the right place, one may thus easily make himself

|

Cabala. |

In Europe, Spain comes most prominently into view in the consideration of amulets, that country being a hotbed of superstition and Cabala.

|

In Europe. |

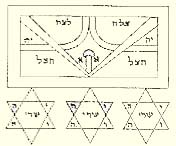

This Amulet, on which [Hebr.] from Psalm xlv. 5 is permuted contains space for a short prayer to be written in, expressive of the particular object to be obtained, and is recommended for use in furthering all business enterprises. It contains the usual shield of David with [Hebr.]. It must be written upon parchment and worn on the left side.

charms as are clearly useless (“Novella” on Shab. 67) In Germany, red cords with corals were worn as protection against the evil eye. Christians employed Jews to make amulets for them; for these had the reputation of being “wise folk.” Strangely enough in the later Middle Ages, Jews attached to their arms, where the phylacteries were applied, amulets containing the names of Christ and the three holy kings (Berliner, “Aus dem Leben der Deutscher Juden im Mittelalter,” pp. 97, 101). Insanity or epilepsy was cured by hanging beets around the patient’s neck. People were warned, however, that the preparation of these amulets would irritate demons. Against miscarriage women carried a stone around the neck, called ~, a word evidently derived from the French enceinte; a hole was pierced through it; it was as large and as heavy as a hen’s egg. These stones, which had a glazed appearance, were found in the fields, and were esteemed of priceless value. A similar purpose was served in antiquity as well as in the Middle Ages by actites. For lightening labor, both Jewish and Christian women wore a piece of a man’s vest, girdle, or other clothing. Luther relates that a Jew presented Duke Albert of Saxony with a button, curiously inscribed, which would protect against cold steel, stabbing, or shooting. The duke made the experiment on the Jew, hanging the button around his neck and then slashing him with a sword (Guedemann, “Gesch. des Erziehungswesens und der Cultur der Juden in Frankreich und Deutschland,” pp. 205, 207, 214, 226, Vienna, 1880). The Italian coin, with its abracadabra-like inscription, described by Guedemann (“Gesch. d. Erz. und der Cultur der Jud. in Italien,” p. 335), was probably of Jewish, and not of Christian, origin. The medallion bears on the one side the words below,

Dilling Exhibit 286 Begins |

[page 549] the Hebrew transliteration of “Majestas YHWH regis domini mei animum benignum mihi foveat” (May the majesty of YHWH foster a kindly disposition in my lord the king toward me). Upon the other side is

“Majestas YHWH animum mei regis ad me inclinet” (May the majesty of YHWH incline the king’s soul to me).

The expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 caused the dissemination of the Cabala far and wide through the East and the West. Their unexampled sufferings served to foster their mystic bent more than ever. The Holy Land, as far as repeopled by Spanish exiles (notably Safed), became the hotbed of the most abstruse secret lore, which favored, among other things, the employment of amulets. From Turkey on the one side, and from Italy on the other, the Cabala spread to Poland and lands adjacent; Hasidism arose there and flourishes there today. This mysticism also prepared the ground for amulets, so that there are whole books devoted exclusively to kemi‘ot still extant in manuscript (compare Benjacob, “Ozar ha-Sefarim,” p. 530).

|

The Eiben- |

It is a curious fact that in all the voluminous discussion, the only point at issue was the employment of the false Messiah’s name in these amulets; not a voice was raised against the folly of amulets in general. The common impression probably was that they could do no harm and might serve as spiritual stimulants in the way of the wearer’s reassurance and mental comfort. This widespread discussion, however, marks the turning-point in the history of the medieval faith in amulets; since then it has gradually diminished and may now be said to be [page 550] practically extinct except in the Orient. The “Shulhan ‘Aruk” does not forbid amulets (see “Orah Hayyim,” §301, 24-27; §305, 17; §334, 14; “Yoreh De‘ah,” §179, 12). It is important to note the fact that the Jews, the “people of the Scripture”, employed mainly written parchments for such purposes, not bits of wood, bone, stone, or other natural objects.

Modern Judaism of course approves the sentiments of Maimonides, who pronounced against them; he denies them all potency or virtue whatever (“Moreh”, iii. 37), and speaks of the “craziness of the amulet-writers, who hope to accomplish miracles by permutations of the Divine Name” (ib. i. 61, end).

BIBLIOGRAPHY: On the Eibenschütz controversy, see the collected pamphlets [Hebr.], Lemberg, 1877; Eibenschütz’s own defense, [Hebr.], Altona, 1755; Graetz, Gesch. D. Juden, vii, note 7.

[Caption under the drawing of the circular amulet:]

This Amulet is claimed to be well approved, and protects the lying-in mother and her child against witchcraft, the evil eye, and demons, and is given in "Raziel," with explicit directions for use. Its authorship is ascribed to Adam. The four words outside of the circle are the names of the four rivers issuing out of paradise, Gen. ii 10. In the circle are Psalm, xci. 11; the names of Adam and Eve; also [Hebr.], which is equivalent to [Hebr.], Eve (in the [Hebr.] system, see AT-BASH, [Hebr.]; then [Hebr.], probably a misprint for [Hebr.], the female demon mentioned in Isaiah xxxiv 14; then come "the first Eve," and names of angels and of God ([Hebr.] = [Hebr.]: in this permutation each letter is represented by the next succeeding letter of the alphabet, thus [Hebr.], [Hebr.] etc.). Outside of the shield of David stand the initial letters of the well-known prayer by Nebvuia b. ha-Kana, [Hebr.], also the words, [Hebr.], "May Satan be torn asunder!" the innermost space finally contains words from Ex. xi. 8, and permutations of [Hebr.], a mystical name of God.

Dilling Exhibit 287 Begins |

[captions in pictorial foldout]

- AMULET FOR PROTECTION AGAINST

LILITH

(From the “Sefer Raziel.”) - SILVER MEDALLION WITH [Hebr.] ON OBVERSE, AND DAVID’S SHIELD ENCLOSING FLEUR-DE-LIS ON REVERSE. 2 5/8 × 1 7/8 in.

- GOLDEN HAND USED FOR PROTECTION AGAINST THE “EVIL EYE,” WITH [Hebr.] IN THE PALM. 2¼ × 1 in.

- PARCHMENT WITH INVERTED PYRAMIDAL INSCRIPTION AFTER THE STYLE OF ABRACADABRA. Diameter 17/8 in.

- PARCHMENT WITH PERMUTATIONS OF [Hebr.] AND [Hebr.] 9¼ × 1¾ in.

[Figs 2, 3, 4, and 5 reproduced courtesy of the UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM, Washington, D. C.]